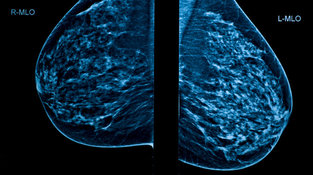

Yesterday evening NPR reported on a recent publication by the British Medical Journal. NPR stated that "mammograms don't reduce the number of women dying from breast cancer, according to a large and long-term Canadian study." I located the original publication and read it in its entirety. Twenty five year follow-up for breast cancer incidence and mortality of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study: randomised screening trial BMJ 2014; 348 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g366 (Published 11 February 2014) Article link: http://www.bmj.com/content/348/bmj.g366 A well-respected radiologist and authority on mammography, Daniel B. Kopans, M.D., wrote a very informative rebuttal. Anyone concerned about the recent BMJ publication regarding the Canadian study should take to heart the comments of Dr. Kopans. Daniel B. Kopans, Professor of Radiology Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts Having been one of the experts called on in 1990 to review the quality of their mammograms I can personally attest to the fact that the quality was poor (1). To save money they used second hand mammography machines. The images were compromised by scatter since they did not employ grids for much of the trial. They failed to fully position the breasts in the machines so that cancers were missed because the technologists were not taught proper positioning, and their radiologists had no specific training in mammographic interpretation. The CNBSS's own reference physicist wrote: "..in my work as reference physicist to the NBSS, [I] identified many concerns regarding the quality of mammography carried out in some of the NBSS screening centers. That quality [in the NBSS] was far below state of the art, even for that time (early 1980's). " (2) In this latest paper (3) the authors gloss over the fact that only 32% of the cancers were detected by mammography alone. This extremely low number is consistent with the poor quality of the mammography. At least two thirds of the cancers should be detected by mammography alone (4). In their accompanying editorial (5) Kalager and Adami admit that " The lack of mortality benefit is also biologically plausible because the mean tumour size was 19 mm in the screening group and 21 mm in the control group....a 2 mm difference." Poor quality mammography does not find breast cancers at a smaller size and earlier stage and would not be expected to reduce deaths. The documented poor quality of the NBSS mammography is sufficient to explain their results and all of the above disqualifies the CNBSS as a scientific study of mammography screening, but it was even worse than that. In order to be valid, randomized, controlled trials (RCT) require that assignment of the women to the screening group or the unscreened control group is totally random. A fundamental rule for an RCT is that nothing can be known about the participants until they have been randomly assigned so that there is no risk of compromising the random allocation. Furthermore, a system needs to be employed so that the assignment is truly random and cannot be compromised. The CNBSS violated these fundamental rules (6). Every woman first had a clinical breast examination by a trained nurse (or doctor) so that they knew the women who had breast lumps, many of which were cancers, and they knew the women who had large lymph nodes in their axillae indicating advanced cancer. Before assigning the women to be in the group offered screening or the control women they knew who had large incurable cancers. This was a major violation, but it went beyond that. Instead of a random system of assigning the women they used open lists. The study coordinators who were supposed to randomly assign the volunteers, probably with good, but misguided, intentions, could simply skip a line to be certain that the women with lumps and even advanced cancers got assigned to the screening arm to be sure they would get a mammogram. It is indisputable that this happened since there was a statistically significant excess of women with advanced breast cancers who were assigned to the screening arm compared to those assigned to the control arm (7). This guaranteed that there would be more early deaths among the screened women than the control women and this is what occurred in the NBSS. Shifting women from the control arm to the screening arm would increase the cancers in the screening arm and reduce the cancers in the control arm which would also account for what they claim is "overdiagnosis". The analysis of the results from the CNBSS have been suspect from the beginning. The principle investigator ignored the allocation failure in his trial and blamed the early excess of cancer deaths among screened women on his, completely unsupportable, theory that cancer cells were being squeezed into the blood leading to early deaths. This had no scientific basis and was just another example of irresponsibility in the analysis of the data from this compromised trial and he finally retracted the nonsense after making front page headlines (6). The compromise of the CNBSS trial is indisputable. The 5 year survival from breast cancer among women ages 40-49 in Canada in the 1980's was only 75%, yet the control women in the CNBSS, who were supposed to represent the Canadian population at the time, had a greater than 90% five year survival. This could only happen if cancers were shifted from the control arm to the screening arm. The CNBSS is an excellent example of how to corrupt a randomized, controlled trial. Coupling the fundamental compromise of the allocation process with the documented poor quality of the mammography should, long ago, have disqualified the CNBSS as a legitimate trial of screening mammography. Anyone who suggests that it was properly done and its results are valid and should be used to reduce access to screening either does not understand the fundamentals, or has other motives for using its corrupted results.

1 Comment

|

AuthorJulie S. Gershon, M.D. Archives

October 2023

Categories |

|

J Gershon Breast Imaging

|

21 Arch Rd. Avon, CT 06001

|

P: 860.673.8379 F: 860.271.8025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed